You’re probably expecting me to talk about how a CEO got shot. But I want to talk about videogames first.

Let’s say you’re playing Mario Kart. Aside from the fun items, you probably drive in-game like real racers do: build speed on straightaways. Hug corners, but stay off the out-of-bounds. Above all: avoid crashing into the walls. For years, this is how everyone played the game.

But then, one day, after thousands of hours of playing, someone found a glitch. They’d driven out of bounds, and instead of penalizing them, the game warped them forwards, closer to the goal. They didn’t know how it happened. They uploaded a video to show others.

Could this be replicated?

The answer: yes. It took a while, but soon people were able to replicate the trick. Then, people started looking for other exploits. Unconventional movements turned into time-savers. Jiggle the control stick on a straightaway to gain speed. Ram into obstacles and use them as ramps. And so on.

Each each time a new glitch was uncovered, experts incorporated it into their strategy. Gamers call this the metagame, or simply the meta: the game within the game. The new ‘correct’ way to play. You might look at Mario Kart and see a racing game. But the observant player sees Mario Kart simply as the scenery against which a completely new meta-game is being played.

In America, political or ideological killing (I include assassinations and racist mass shootings here) implies a kind of meta-game played between killers and the media.

‘Winning’, for a killer, is less of a win/loss binary than it is a fuzzy scale of audience attention. How many points can you get for you and your cause?

Shooter moves first: kill people; perhaps also yourself. End turn. Now, the media’s move: This is a more delicate balance. Report the facts, while minimizing the shooter’s score.

Journalists are the first of the shooter’s ‘audience’ who the cops will talk to, and so it is our job to filter the violence for mass consumption. Make some sense of the who-what-why, but also mitigate the damage: It is a recent-ish journalism best practice to avoid naming the shooter. We’re asked to focus on the victim, their lives, their stories. The motivation is honorable: mass shooters especially want attention, and this denies them that. Theoretically, this also reduces copycats. This is the same reason we don’t publish manifestos (but we maybe quote excerpts).

Each round of the game played out the same way: Body count. Headlines. Interviews. Prayers. Thoughts. The audience forgets, and mentally prepares: round two begins soon. Maybe next week, maybe tomorrow.

But as of the morning of December 4th, there is now a new theoretical high score. Everyone* loves Luigi.

Could this be replicated?

Probably. I can think of three small signs that something has shifted.

The first is the language we’re using: hardly anyone is bothering to use the victim’s name.

Even most news article headlines simply refer to him as the ‘United Healthcare CEO’; if that. More often, he’s reduced to a ‘healthcare CEO’ or simply a ‘CEO’. I did this in the beginning of this article, by the way: you probably didn’t even notice. Nobody seems to care!

And yet everyone knows, and uses, the alleged killer’s name.

There are a couple of factors here: the first is chance. It just so happens that the victim’s name — Brian Thompson, by the way — is a forgettable one. And then we have Luigi Mangione. Just the name ‘Luigi’ — and my apologies to the Italians out there — makes most people think of the green guy in the Mario games. Memes were a pre-existing condition in this case, but now that we have a(n alleged) name, the condition is terminal.

And then there’s the pictures. Luigi feels like a real person. He has a digital footprint. We know what books and podcasts he liked, but also we see pictures of him hiking, enjoying life. Smiling. Compare that to the one or two photos we have of Brian Thompson, doing that forced half-grimace you do when you bump into a coworker whose name you don’t know in the office cafeteria.

Again: it is pure chance that we have a photogenic (alleged) killer with a memorable name, versus a generic corporate LinkedIn avatar. But it’s relevant.

The peak of this is probably last week’s SNL cold open. Chris Rock joked about the murder, saying ‘sometimes drug dealers get shot’. He name-checked Luigi, twice. Then, he said: ‘I have real condolences, for…you know…’ he paused, as though struggling to recall the name, and then after an awkward moment, gave up and finished his sentence: ‘…the healthcare CEO’.

On top of all that, let’s stack a second sign that the game is changing:

Journalists are feeding audience demands, even more obviously than before.

Speaking of video games: an NBC News article last week connected the murder to the fact that Luigi Mangione played Among Us, a game that probably more American teenagers have played, and for longer, than ‘Duck, Duck, Goose’.

(not kidding. Consider: it is a 500M+ downloaded game that went viral during quarantine, when kids literally could not play IRL games in class).

It’s a silly article, but I know why it was framed that way. In high profile shootings, a reporter is put in a strange position. You want to prove you can ‘respond’ to ‘the moment’. So you hit the phones. Call every number you find. Extract a small factoid. A middle school report card. A restaurant receipt. Anything.

‘The audience’ often says they want to know the stories of the victims. But their clicks say otherwise.

‘The audience’ wants to know more about the killer, and NBC simply tried to feed the beast, by publishing an article with no new information other than a silly tidbit about a children’s game.

In the absence of facts, the audience generates their own #content. There’s a video circulating of a guy doing a clean-as-hell kickflip over a railing. It kinda looks like Luigi if you squint. It’s not Luigi. But people share it anyway without checking because they want it to be him.

On the other hand, there seems to be little interest in humanizing ‘the CEO’. There is no viral, collective effort to share stories about him. It’s a passive process. Maybe it mirrors the passive dehumanization people have felt: sick, scared, trying to navigate an insurance company’s impenetrable vertical maze of phone options spoken in a clear, sterile voice:

Your call is important to us. Please listen carefully, as our options have changed.

So NBC sees the market demand. Nobody is making ‘CEO’ content, but Luigi #content is a hit. Let’s give the people what they want.

Is this supply-and-demand relationship (audience capture) so strange? In the country in which police departments make their own ‘True Crime’ podcasts?

Is it really so strange that the NY Times has run dozens of articles on this, and has yet to cover a stabbing death, a couple miles away, of an immigrant kid?

Which is is more shocking? Which will get more clicks?

‘Importance’ is not an objective metric.

This week, Variety announced that a new documentary about Luigi was in development. Three hours later, they announced another one. Later that afternoon, a third was reported. Wanna get in on the action? The official IG @luigidoc_tips might be your chance.

The CEO hadn’t even been in the ground for a week.

America is a market which demands to be presented with blood, but also bores easily. So it occasionally bites itself, to see if it can bleed in a novel way.

The third sign: the memes.

First, let me do the paragraph where I tell you about the smart things that have already been written on the topic: here’s a nice bait-and-switch headline that explains things you already know about why American healthcare is bad. Here’s a jokey, satirical response by former colleague(?) Eddie Huang, who suggests forming a political party around the shooter. Jason Koebler, another former colleague now at 404 media, elaborates on the futility of trying to write about this stuff. Taylor Lorenz was the first to provide a coherent analysis of why people were memeing and celebrating the shooting.

I’m going to ignore the big legacy publications and TV stations who are telling us why it’s morally wrong to make memes and jokes, because that’s precisely what the audience is doing: ignoring them. Who cares? Culture movers don’t read the NYT. That’s for CEOs.

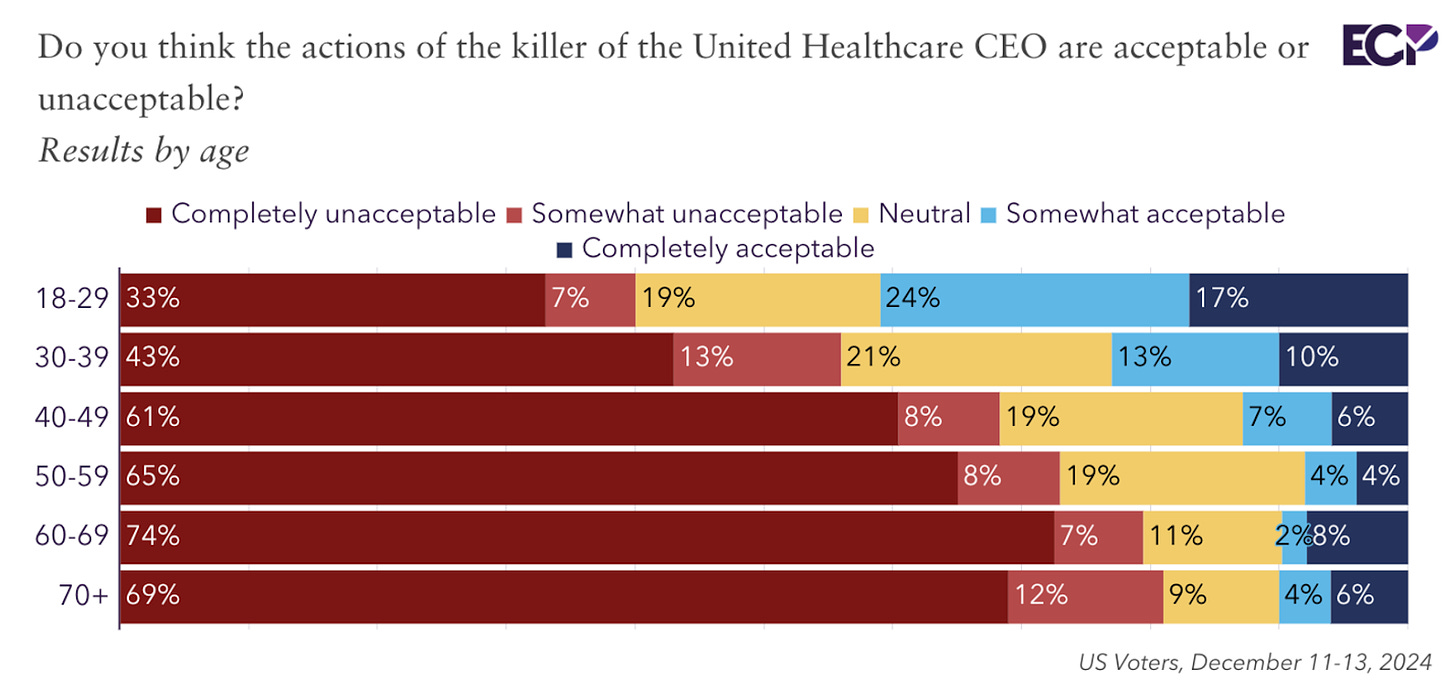

I’m joking a little. But it brings me to a huge caveat. And this is where I pick up that asterisk from above. Polling shows that a lot of Americans do not like Luigi Mangione.

I think the audience laughter at the SNL cold open shows that if Americans disapprove of extrajudicial killing, at least the moderate liberal class doesn’t feel too bad about this instance. But let’s just take the polling at face value, and agree: the memes, the folk ballads, the rap songs, don’t represent all, or even most, Americans. That’s just a loud (and young) minority.

Sure. But when has a quiet (and old) majority ever moved culture? Isn’t American history a long list of a loud minority influencing the undecided masses? If you were still a child when Facebook invented the ‘like’ button, wouldn’t you be more interested in winning over your Terminally Online peers than swaying someone who needs a Wall Street Journal subscription to form an opinion?

What if your audience isn’t the wider American public?

What if the new meta is to speak to the influencer demographic?

I should clarify the title of this thing. Saying ‘the game has changed’ is maybe a little misleading. When the Mario Kart meta shifted, it wasn’t because gamers were physically reprogramming the code. They were simply exposing flaws that already existed in the system. They just figured out how to work them to their advantage.

Same thing here. The game has always been this way. We are just seeing it more clearly.

Another caveat: I’ve seen some people hope/fear this is the beginning of a class war. I don’t think that is a sure thing.

I think multiple-CEO Elon Musk’s continued popularity, as well as Trump being elected again, should disabuse us of any illusion that Americans are ready to unify against rich people. Sure, it’s possible, and people do get used to violence very quickly.

But I think the only reliable prediction we can make here is something much more neutral, and thus more dangerous: the feeling that a potential new infinite attention glitch has been discovered.

Maybe the next assassin will be a leftist. Or a nationalist. Or something incoherent. Maybe they’ll be angry at the healthcare system. Or angry at immigrants. Or something else.

Racist mass shooters often expect that their actions will start a larger race war. This has been pure delusion: it never happens. The public, even other racists, shun them.

But the ‘CEO shooter’ achieved something – intentionally or not – that most killers have only dreamed of: not only attention, but gratitude. Being compared to Jesus is now on the table.

The Arrest of Christ, German artist, 1480-1495, 📸 by @1ontapdigital

— ArtButMakeItSports (@artbutmakeitsports.bsky.social) 2024-12-20T03:39:10.185Z

The next shooter probably won’t reach these heights. The next shooter may not be successful in winning over his, or any, public. But you can bet that the next shooter will be trying to replicate Dec 4th.

The last thing I’ll say: I don’t know that we can realistically say either that Brian Thompson’s murder was wholly senseless, nor can we say that he ‘had what was coming to him’, without also acknowledging what put him, and the shooter, together on the street that morning. Both men are symptoms of a chain of passive decisions that went wrong a long time ago.

The shooter allegedly used a ‘ghost’ gun – an American cultural product. A product of an obsession that would not have festered like this if we had done something, anything, over the last few decades. American healthcare is objectively a deadly nightmare. We’re the richest country in the world. If we had done something, anything, a lot of people could still be alive. Including ‘the CEO’.

Well, I guess some people did ‘do something’. They voted. Told their stories. Some even protested. Maybe that's part of the game. Of Capitalism, I mean. To make us feel like that is enough.

(to make you feel good when you ‘make progress’ — so that you forget that the game is still fundamentally about going in circles.)

So: who do we blame when the game plays out the way it was programmed to? Where is the line between good guys and bad? At the C-Suite? Directors? Managers? Doctors? The people who voted for the ‘wrong’ politicians?

We let these laws stand. We let these companies continue to exist. We clicked the articles. We wrote the articles. The blood is on everyone’s hands. We made this game.

Who loses next?